Briggs Cunningham is a hero of mine. Here's a man who was born of privilege (his father was a wealthy financier) who could have spent his lifetime driving expensive cars and chasing women; instead, he spent it building expensive cars and chasing the Italians at Le Mans. Oh yeah, he also won the America's Cup Yacht Race. What did you do today?

He raced Ferraris early in his career, and integrated the melding of power and lighter weight into his own design. Briggs actually was the first in America to import and race a Ferrari, a car that was fierce, yet somehow adorable after Cunningham "personalized" it...

We know he was a helluva driver (in the 1952 24-Hours of Le Mans race, Briggs drove 20 of the 24 hours!) and he certainly appreciated the top of the line cars, so what does the Cunningham C1 and C2 tell us about the man and his vision?

Let's take a look at the overall design.

|

| Briggs Cunningham beside his C1 |

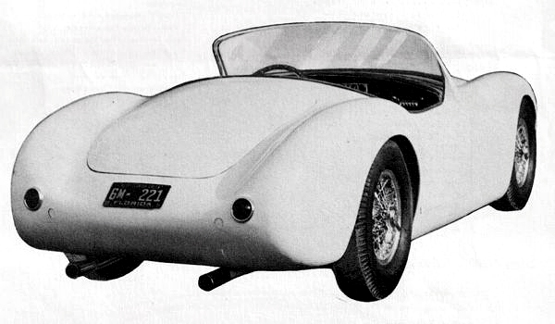

It's a good-looking car; muscular, sporty and aggressive. A striking design for it's time.

And also very similar to another car... the 1949 Ferrari 166 MM Touring Barchetta

Briggs Cunningham was more familiar than any American with race Ferraris. He went to Italy, he raced against Ferrari, he imported the first. So to think that he didn't know about this stunning roadster is inconceivable. It was exhibited at the 1949 Paris Show, and was the first car designed by Enzo in house with Barchetta (roadster) coachwork by Carrozzeria Touring of Milan. And on top of that, it won the 1949 event that Briggs chased his entire racing life, the 24-hours of Le Mans.

But still, if you're going to pay tribute, make sure you emulate the baddest of the bad.

Where were the distinctions made? First off, the engines, of course. Cunningham went with the most American of power-plants, the Cadillac 331. This was the initial concept, but Cadillac ended their development partnership quickly when they realized they were running low on spare engines (according to Brigg's account) and Briggs switched to the hemi. They were new, powerful, and Chrysler offered them to Cunningham at 40% off, the best deal Briggs could get. Ferrari ran their own V12.

The interiors were very similar. Looking at both, it's as if they were made by the same company. Each features a pair of bolstered seats, plain but highly-functional.

But it was in the functional yet striking dash detailing where the Italians pulled away. The Ferrari builders were no fools, and went with an established gauge company, Jaeger. Jaeger had a fine tradition of top-quality instrumentation and time-keeping for Jaguar and others.

| |

| Ferrari 166 dashboard gauges |

Cunningham went the hot-rodder route. His is a simple display filled with Stewart Warner gauges.

This is really as plain as you can get. A machined billet steering wheel, tiny shifter and look, a radio! This is the kind of set-up that hundreds of backyard builders were putting in their cars, and it's no wonder that Briggs went with upscale foreign instruments later on. Here we have straight-up Stewart Warner Wings insignia gauges, except, and we have seen this before, a Sun tachometer. I'll put together a larger piece on why this was happening at this time down the road.

So what's the verdict? Was Briggs Cunningham a gifted mechanic? There's no doubt that his early partnership with mechanical genius Alfred Momo produced some top-shelf race cars, and though they never could get the flag at Le Mans, they prevailed almost everywhere else at one time or another.

Was he an artist? This is hard for me to say, being an ardent admirer of this racing giant, but I'd have to say no. His design is a pale image of the great Carlo Felice Bianchi Anderloni 's concept , and the details, like in the dash and interior, which usually show the mark of a master, are mundane and pedestrian. It's no surprise that he quickly realized that to sell more of them, he needed to update his look, and he later upgraded with a concept from Vignale of Italy, based on the great Michelotti's design. They cost $2700 apiece for the bodies, which Cunningham sold complete for $9500 for the coupes, and $10,500 for the convertibles.

After a brief run of five years, the increasingly higher expense of manufacture (they had to buy black-market steel from France during the Korean War) and the IRS laws limiting the non-profit status of the Cunningham "hobby" conspired to shut down the "C" series. But Briggs showed it could be done, that there was a passion for an American representative in the road race/tourer field, and he paved the way for the Shelby Cobra line and others to produce world-beaters in speed and style.

He's still my hero.

Thanks to my good friend Geoff Hacker, the impresario of all things Fiberglass, for the high resolution Cunningham shots, and be sure to check out his definitive site, Forgotten Fiberglass.

No comments:

Post a Comment